An Introduction to Ladies Almanack

It was shortly before New Year’s when I first went searching for a source for the Gaming Like It’s 1928 game jam. My first instinct was a 2D vintage flight sim – it was the year after Lindbergh first crossed the Atlantic and there were no shortage of newly-public domain airplane illustrations.

I had stumbled across Ladies Almanack in lists of 1928 books, but immediately discarded it when I realized there was no way I would be able to understand it – let alone translate it into a game – in one month.

But I kept thinking about it. I was fascinated by how much English-language lesbian literature I was coming across while looking into this year – and how much of it was specifically coming out of Paris. 1928 was a “banner year” for lesbians, apparently. And it turns out this was due to a confluence of circumstances – increased opportunities for women in general, obscenity laws and censorship in America and Great Britain driving queer or controversial writers and artists into self-exile in Europe, and the favorable post-war exchange rates that brought wealthy Americans to France, who then became patrons for these artists.

By 1928, the “Lost Generation” of artists in general had years to hone their crafts, with mentorship, financial support, a thriving community in cafes, clubs and literary salons, and opportunities for private publications for works that wouldn’t make it past censorship.

But, by that time, Natalie Barney, an American railroad heiress, had also been hosting weekly Friday salons in the Left Bank of Paris for almost two decades. And her mentorship had fostered all kinds of artists, but particularly female, and particularly queer.

So, in a way, a wealth of English-language lesbian literature coming from Paris was almost inevitable in 1928.

And 1928 was also the last year it could be.

The stock market crash in America, the rise of fascism in Europe, the occupation of Paris, and the anti-feminist culture that followed World War II set back these women’s lives, and queer literary culture, for decades.

As I learned more about this community in 1928 Paris, I realized that Ladies Almanack could be not a roadblock but a lens from which to view it. So, with the help of some historical references and scholarly articles, I did finally manage to read the book.

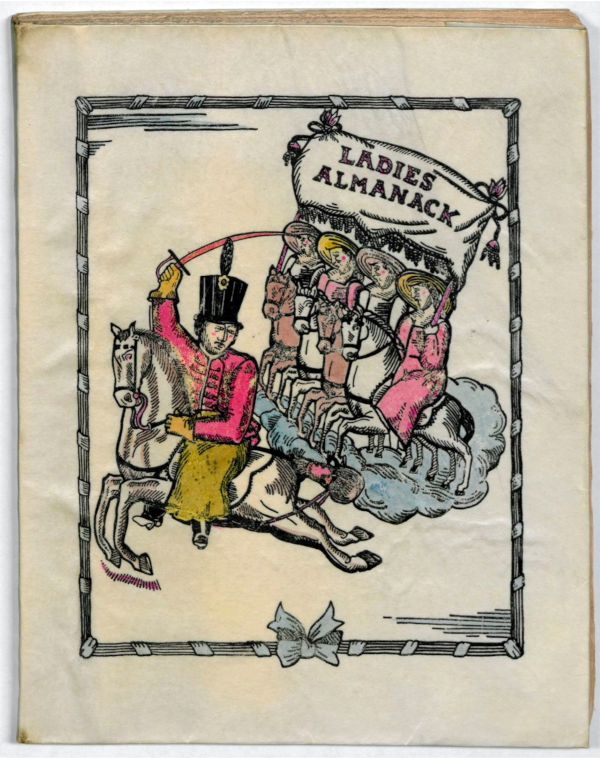

Ladies Almanack

Ladies Almanack is a beautiful but very difficult read – even by Modernist standards. But, past the baroque metaphors and Joycean sentences, the command of language is masterful. I’ve never read anything like it. Djuna Barnes manages to twist the male-centered, over-detailed explicitness of the Modernist movement into lesbian satire that’s unmistakably written by, and for, the female gaze.

On top of that, Ladies Almanack is also a radical and unapologetic depiction of women just… living their own lives.

Using the trope of an instructive monthly almanac, it interweaves tales of the daily lives of a friend group in the expatriate lesbian community in 1920s Paris with a subversive biblical origin story for the first woman born “with a difference” (spoiler: she was conceived when an orgy of angels melded together and laid an egg) and the life story of the Sapphic patron saint, Dame Mussett (based on Natalie Barney).

It was first published in 1928, and only in France. Barnes was already a best-selling author in America at the time, but she had good reason to believe Ladies Almanack would not make it past the censors. Only 1,050 books were printed, with the author herself smuggling copies in to sell in the United States and England.

It was almost 50 years before a second edition was published. Even today, it can be difficult to track down a copy, since even the ebook is currently out of “print”. (However, there is a copy available online at the University of Maryland: it’s a rare fully-digitized first edition with illustrations hand-painted by the author. I highly recommend taking a took!)

I think it would be subversive even today, when we are barely getting beyond the “evil, dead lesbian” trope (which itself was a legal requirement to bypass censorship). But, in the early 20th century, Ladies Almanack feels almost anachronistic. It left me fascinated by the world that must have existed in 1920s Paris to foster such joyful, forthright, and humerous depictions of queer women.

Creating this game was a chance to explore a small piece of that world. According to the plan for the full version of the game, you can walk the streets in the same neighborhoods and sit in the same cafes as Barnes and her friends, and get a chance to attend Natalie Barney’s famous Friday literary salon that exists at the core of this world.

Get Ladies of the Almanack

Ladies of the Almanack

| Status | In development |

| Author | dandelion dino |

| Genre | Visual Novel, Adventure, Educational |

| Tags | Female Protagonist, Historical, LGBT, Side Scroller, Walking simulator |

| Languages | English |

| Accessibility | Configurable controls |

More posts

- Credits and LicensesFeb 02, 2024

From

From

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.